How to implement a text mining engine

There are various text mining libraries, packages and tools available, many of them as freeware. Yet, when it comes to putting it all together in an enterprise environment, there is actually not too much information available on the web. This article is about how I would design a general-purpose text mining engine that is fit for today’s standard Java-stack enterprise environment and the typical problems one encounters in these environments. A lot of what I write below is from hands-on experience with existing tools and the typical difficulties I had.

Tasks and components

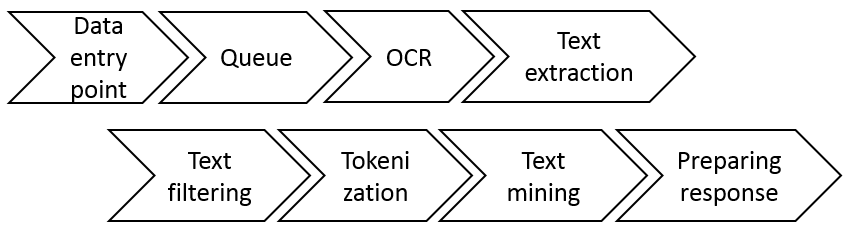

Text mining tasks typically follow a similar.

- Data must be obtained from a data source, for example a file system or document database.

- Sometimes, the the original documents have only been scanned and saved as image files (e.g. TIFF files, or PDF/Word docs containing images). In such situations, OCRing (optical character recognition) is required for preprocessing the document to text data.

- Often, the input files are not stored as plain text data, but must first be converted from an original file format (often PDF or Word) into plain text files.

- Filtering is applied to remove undesired text. For example, in HTML/XML files all markup is removed.

- Once plain/raw text data is obtained, the text is tokenized with the support of a text mining library. The unit of work can be individual words, sentences, or paragraphs.

- The core text mining tasks are executed on the tokens. This is highly specific to the problem at hand. Typical tasks involve entity extraction, calculating term frequency/inverted document frequency (TF/IDF) measures as an input to algorithms like bag of words and so on.

- An output string containing the relevant information is assembled. This is either stored somewhere or sent back to the originator system as a response.

From the tasks above we can deduce some of the components our text mining engine must contain.

- A component to receive data (push), or load it (pull) from somewhere. After processing we might also want to store or send processing output somewhere.

- Possibly an OCRing component.

- A component that extracts raw text from various file formats.

- A filtering or text cleanup component.

- A tokenization component.

- The core text mining component(s).

- A component assembling a response that can be sent to the client.

- A component that glues all of this together.

Furthermore, we need to be able to handle irregular demand patterns. Especially OCRing uses a lot of CPU power, and we cannot fill up our server endlessly with additional load. Hence, we also want to use a queue where we can enter new text mining tasks, which can be polled regularly for a status update. A queue also allows us get away from synchronous request handling, i.e. to shut down network connections in between sending a task and receiving a response.

These are the components/tasks we identified so far.

Architecture

Standard JEE architecture

It should already be obvious that there are several software design patterns which could potentially be useful in such a situation, for example:

- chain of responsibility pattern,

- pipeline and filter pattern which is closely related to chain of responsibility,

- decorator pattern as a potential alternative to pipeline and filter or chain of responsibility,

- parameter object pattern to pass values between various components/tasks,

- builder pattern to build the pipeline of components/tasks.

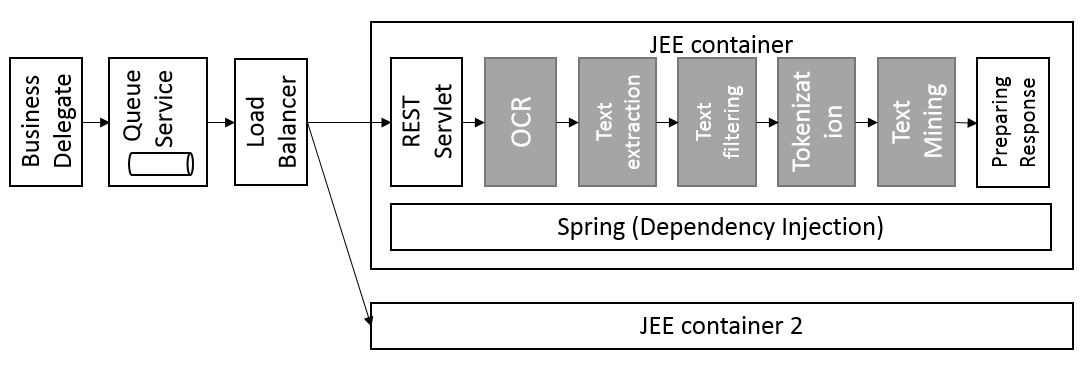

The next chart shows how I would design such a system relying on a rather classical JEE architecture.

The server offers a REST API (servlet) to the client. A business delegate might be used in the client to cover up the connection implementation details. Between client and server one could add a load balancer to scale up horizontally. Furthermore, a queue is added somewhere in the stack (could also be inside the JEE container). Tasks are first added to the queue before being processed further. The queue service can be polled to obtain an up-to-date status of one’s task or the response object once the task completed. A pipeline and filter pattern is used for the gray components. They all implement the same interface:

public interface Processor {

public void process(DocumentContext ctx);

}A parameter object pattern is used to pass one object from one processor to the next. Class DocumentContext could for example contain a map of key/value pairs, where the key is the name or ID of the particular Processor and the value the processing output. Each processor simply adds new output to the DocumentContext. Prior output is only deleted in exceptional cases (e.g. throw away binary data that was required as an input to the OCRing processor).

The second JEE container is simply a second identical set up running in a different virtual machine to handle peak loads through the load balancer. More VMs could of course be set up.

Processors

Every Processor should be implemented as a simple Java bean object, i.e. it should have an empty constructor plus getters and setters for every object property. A dependency injection framework like Spring is used to “glue” all Processors together. Either every Processor keeps a reference to the next in command, or all messages are passed solely through the embracing framework. I personally prefer the second option for reasons that will hopefully become more clear later on. In general I highly recommend implementing each processor without state. A stateless processor offers many advantages over stateful designs. The most important advantage is the inherent thread-safety. Running multiple text mining jobs in parallel in the same JEE application requires the code to be safe for multi-threading, which can be achieved much more easily with stateless designs.

This is an inexhaustive list of various open-source projects delivering value for the different processors.

| Component/Processor | Open Source Project | Queue | RabbitMQ, Kafka, ActiveMQ, Kestrel | </tr>

|---|---|

| Dependency Injection | Spring, Guice |

| Pipeline and filter | Apache Commons Pipeline, Apache Camel |

| OCR | Google Tesseract |

| Text extraction | Apache Tika |

| Tokenization & Text Mining | OpenNLP, Stanford NLP, Mallet, WekaNatural Language Toolkit (NLTK, Python) |

To OSGi or not

It would also be possible to make every Processor an OSGi bundle to allow dynamic updating of existing bundles. This approach was actually taken in the Apache Stanbol project. However, I’m not so much convinced of this architectural choice. Why exactly should one be able to update text mining modules on the fly during runtime? If it were just a few parameters per text mining module that might change during runtime, then certainly implementing OSGi for every processor is a huge overhead, there are better ways to handle changing parameters. If you work however in an organization with a typical JEE technology stack then most probably you also have the three environments for development, testing and production. New text mining modules require thorough testing and an official rollout, after all it’s productive code! Of course, rolling out without downtime is a nice idea, but isn’t hot deployment nowadays a standard feature of most modern JEE containers anyway? What do you really need OSGi for? And if you’re still not convinced OSGi adds little value but much unnecessary complexity to your application, consider this: Assume a running and unfinished text mining process. While the process is still ongoing you initiate an OSGi bundle replacement (or hot deployment, for that matter…). What is the exact semantics of your running text mining task now? What is supposed to happen with it? Not properly shutting down your application before deployment might actually complicate things significantly. In case you have a persistent queue in place than can handle a bit of extra load you could simply shut down your server temporarily and let the queue fill up with new tasks without anyone complaining. (I didn’t say this is generally a good idea though… .)

Comparison with Luxid Annotation Server

The architecture above is actually similar to Expert System’s (formerly Temis) Luxid annotation server. A significant difference is however that in Luxid the core server - called information discovery and extraction (IDE) server - is implemented as a black box. The Luxid IDE server contains an internal (embedded) Jetty server that is not really accessible to a developer. As a consequence it is not possible to run the Luxid IDE server inside another JEE container, the IDE server is always standalone. For this reason many container-managed features are not available to Luxid developers, and possibilities for performance tuning are limited to what was exposed by the vendor beforehand.

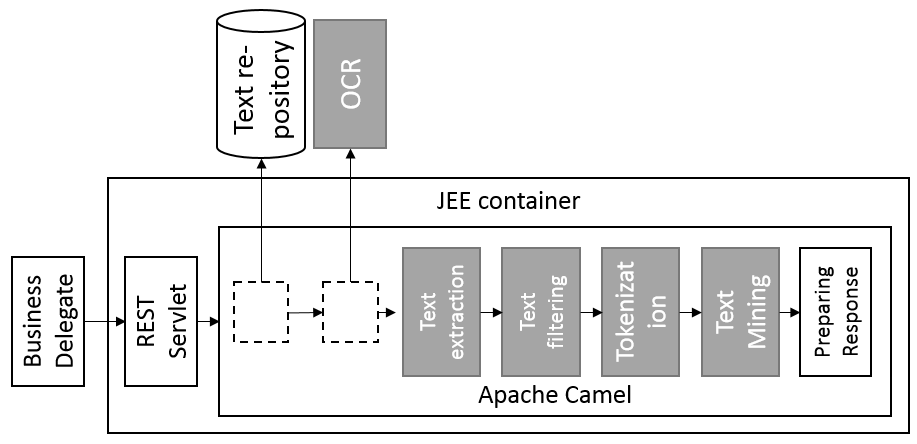

Modular architecture using Apache Camel

The above architecture is not optimal yet. For example, we might want to run OCRing completely separately from all other text mining tasks. Also, a very typical problem in text mining is to load text documents from a source system (database, file system, FTP server, website etc.) and possibly write data back to a target system. And what about implementing non-Java processors? So your text mining expert has developed some code in Python. How can we call NLTK (Python) code to obtain text mining results? In short, we really would like to decouple the various processors even further, so dependency injection is not yet sufficient for what we aim to achieve.

Luckily, there is one framework particularly well suited in our case: Apache Camel. Apache Camel is at its core a routing engine accepting input from a very long list of protocols such as HTTP, FTP, NTFS, etc. This allows loading text files even from remote sources with relative ease, for example load data from an FTP server and then send the processed output to a REST API. Apache Camel uses several of the above mentioned design patterns (dependency injection, builder pattern, parameter object etc.) in combination to achieve loosely coupled systems that are easily changed. It allows the combination of several processors by configuration only (only little coding requried). It can easily be run both inside a standard JEE container as outside in a standalone application. It can call services in remote systems and hence integrate also non-Java applications.

As we can see this architecture is more modular. I have separated the OCR process from the other processor components but left all the other components in the same JEE container where Apache Camel resides itself. This is just a suggestion, of course each processor could run entirely in its own container, there are other combinations possible as well. Whether or not we still need a queue and a load balancer, and where these should be located exactly in the architecture depends a lot on the use case. Apache Camel can be integrated well with different queues.