Implementation of Rhizomes - Part 2

In my last post on the implementation of rhizomes I still suggested using hash maps to store pairings, that is relations. It was just recently that I recognized that there is of course an even simpler and more concise way of storing relations: as a single, long bit string, where a bit is set to 1 if a relation is established.

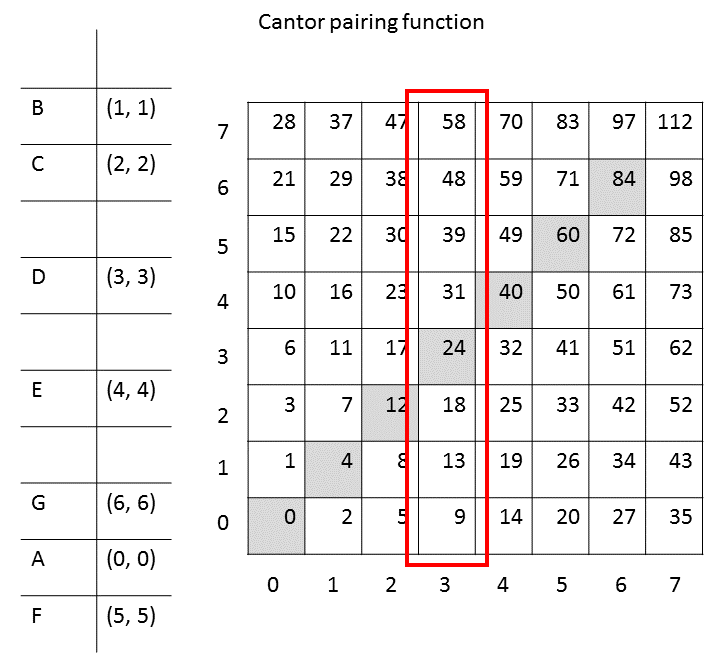

Let us assume for the moment that we use the Cantor pairing function already defined earlier:

Cantor pairing function:

pair(x, y) = z = 1/2 * (x^2 + 3x + 2xy + y + y^2)

unpair(z) = (x, y) = {

x = z - (q * (1 + q))/2,

y = (q * (3 + q))/2 - z },

with q = floor((-1 + sqrt(1 + 8z))/2)For the relation (1, 3) the output will be 11. The only thing we need to do to indicate that there exists such a relation is set the eleventh bit to 1. To save some disk space, we additionally use bit packing such as Concise or Word Aligned Hybrid (WAH) [1]. It is however highly recommended to use a bit packing algorithm that allows to check whether a bit is set without having to unpack and re-pack the string.

This representation results in an extremely storage-efficient representation. Of course we still require a separate data structure such as a bi-directional hash map to store the relation between leaves and the real data.

Now that we got rid of hash maps, how do we efficiently look up all the relata for a given relator? Assume that you have a relation (x, ?). How can we efficiently find out all possible values for ? without having to loop over all bits in the bit string?

Luckily, the Cantor pairing function (and as it turns out also the Szudzik pairing function) have nice symmetries concerning the values stored in rows and also in columns. Take a look at the following figure:

To find out all the pairings for the relation (3, ?) the only bits we need to check are the ones in the third row, that is the values 9, 13, 18, 24, 31, 29, 48… . Finding the regularity behind this row is very simple.

- Calculate the first pairing (3, 0) => 9.

- 3 is the fourth number (starting at 0). Add 4 to the result from the last step: 9 + 4 = 13. Thus, 13 is the next relation (3, 1) => 13.

- Add 4 + 1 to the result from the last step: 13 + (4 + 1) = 18. Thus, (3, 2) => 18.

- Add 4 + 2 to the result from the last step: 18 + (4 + 2) = 24. Thus, (3, 3) => 24.

- 24 + (4 + 3) = 31. Thus, (3, 4) => 31. Et cetera.

If the complete bit string has a length of 10000 then we simply need to check the bits 9, 13, 18, 24, 31, 29, 48… up to and including the 9999th bit to find all the pairings (3, ?). Of course this could be parallelized easily too.

For the Szudzik pairing function, the situation is only slightly more complicated. There, we need to make a distinction between values below the diagonale and those above it. Other than that, the same principles apply. One nice feature about using the Szudzik pairing function is that all values below the diagonale are actually subsequent numbers.

References

[1] Chambi S., Lemire D., Kaser O., Godin R. (2015): Better bitmap performance with Roaring bitmaps. Working paper published at http://arxiv.org/abs/1402.6407.